Awkward interviews are out—bring back the charm

journalism is suffering in a post-awkward interview world

In 2005, Vanity Fair writer Leslie Bennetts walked up the front steps to the Malibu bungalow being rented by Jennifer Aniston and knocked on the door. The actress opened it, gave a smile, and then burst into tears. It was a few months into the public nightmare of her divorce with Brad Pitt being plastered on tabloid and supermarket gossip magazines around the country. Barely a year earlier, Bennetts had interviewed Pitt at his Beverly Hills mansion, where he lived with Aniston. The two had walked her to the car afterwards, leaning on each other in the driveway with arms intertwined as they waved her off.

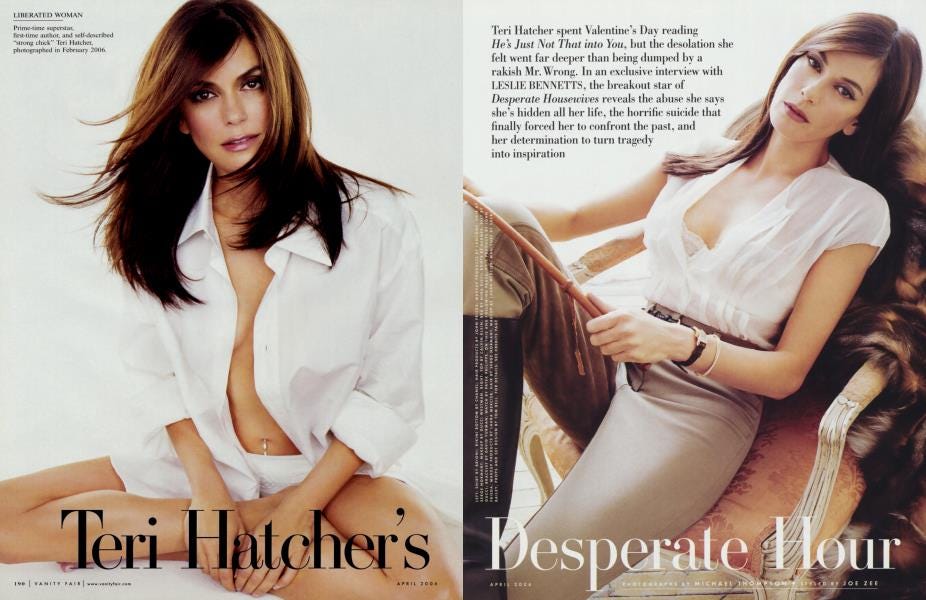

Bennetts sat with Aniston on her deck overlooking the Pacific, conducting her interview amid the sound of the waves. Years earlier, she had sat on a similar deck at k.d. lang’s farmhouse outside of Vancouver for an interview. In 1994, she sat with Debbie Reynolds backstage in her dressing room at two o’clock in the morning. A decade later, in 2006, she would sit in Teri Hatcher’s bedroom as the actress, wearing a head-towel and silicone face mask, sank down into a beanbag and cried to the journalist.

Bennetts’ interviews worked so well because she had a certain charm that won over these celebrities. She created a space for people to relax, open up, and even cry in front of her. Like any journalist, her personality and curiosity were essential tools to get the story she needed.

But while the 90s and 2000s had their fair share of intimate celebrity interviews, it also saw the rise of another journalist format: the awkward interview.

Comedians like Eric Andre would blend discomfort with journalism to create a strange parody of late-night talk shows. In The Eric Andre Show, Andre would start destroying sets in front of guests, have random characters storm the stage, or ask absurd questions.

There’s also Zach Galifianakis’ Between Two Ferns, where he would play an exaggeratedly blunt version of himself that asked A-list celebrities questions like “Do you ever get tired of being so ugly?” or “When you’re in the recording studio, do you ever think, ‘Hey, what if I don’t make something shitty?’”

Andre and Galifianakis’ formats worked so well because they were obvious parody. From the interviewer and the interviewee to the audience, everyone was in on the joke. The celebrity would laugh, play along, or try to one-up their strange host.

But somewhere along the way, the lines between satire and reality in these interviews began to blur. Amelia Dimoldenberg’s Chicken Shop Date series borrows some of this awkward interview energy. Dimoldenberg conducts interviews/dates with blunt questions and an offbeat flirtatious tone. It’s funny, it’s endearing, and Amelia herself is deeply relatable for many viewers. Her awkwardness feels like how most of us imagine we would act if we were sitting across from Andrew Garfield. Her persona is so effective people even occasionally speculate on the relationship she might have with her guests.

Bobbi Althoff pushed this formula even further on her podcast The Really Good Podcast. Her viral Drake interview took place with them both under the covers in a bed, with her mumbling questions in her trademark bored-monotone voice. There’s also the iconic Sukihana interview where Althoff refers to her as a “musician”, causing Suki to argue that she isn’t a “magician or whatever”. As a viewer, I have no idea where Bobbi Althoff ends and where her character begins. The issue with her nonchalant approach is that the line between reality and bit are completely blurred, creating uniquely hard-to-watch interviews. And because her persona leaves little room for genuine curiosity, the “interviews” rarely reveal anything new about the guest.

Another figure riding this awkward interview wave is Adam Friedland. The Adam Friedland Show on YouTube mixes absurdity with political and cultural commentary. His guests, usually prominent public figures or commentators, are faced with his offhand provocative jokes and long pauses. It’s a humor that many of his older or more “serious” interviewees don’t usually understand or reciprocate.

It’s a strangely entertaining format that makes you tune in both for the discomfort of “serious” people like Ritchie Torres and also some surprisingly good journalism on his part. Friedland, though he puts on this slightly-exaggerated persona, is still pushing towards real and important answers. His approach shows how that the awkward interview formula really can produce some meaningful journalism, if done right. But, unfortunately, not everyone is doing this blend of awkward journalism in the same way.

Fans of these kinds of interviews argue that people like Dimoldenberg are unraveling a “celebrity’s persona on screen” and rendering them “completely unfamous” through their awkward approach. They feel there’s a certain authentic air that comes from being interviewed by someone who isn’t being overly serious.

But I feel this trust in celebrities ignores the obvious fact that these are still, at the end of the day, PR stunts. The awkwardness of Dimoldenberg’s dates aren’t revealing some hidden personality in these celebrities, but simply shaping the performance they take on. Garfield isn’t more “authentic” just because he’s eating chicken in a restaurant; he’s simply meeting his interviewer halfway, adjusting his tone to match hers.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to the digital meadow to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.