From Alchemy to Aroma: Exploring Fragrant Women in History

Cleopatra, Catherine de Medici, and other hidden figures; a study on the female contributions to the world of perfume and how they employed scent as a social tool

“Why not drink while we can, lying, thoughtlessly, / under this towering pine, or this plane-tree, / our greying hair scented with roses, / and perfumed with nard from Assyria?”

- Horace, The Odes II, c. 23 BCE

In Greek historian Plutarch’s record of Cleopatra’s visit to Tarsus, he wrote that “perfumes diffused themselves from [her] vessel to the shore, which was covered in multitudes…running out of the city to see the sight”. Marc Antony, who stood awaiting her arrival, was said to have been immediately enamored by the Egyptian queen, many attesting this to her alluring aroma. But what exactly was the scent that Cleopatra used to have crowds of people gather at her arrival and to instantly bewitch Roman leaders? Or what about the revolutionary scents that Catherine de Medici used to help establish the French as the world’s foremost perfumers?

The art of perfumery is not in any way a new or modern invention. The first known recipes for sweet-smelling fragrances date back almost 6000 years to the Mesopotamia’s. Perfumes were used in many aspects of day-to-day life, it wasn’t simply a tool for hygiene. Aromatics were used for their medicinal properties and for worshipping in the temples. As the wealthy used perfume to mask their scent, it became a status symbol among the ruling classes. This idea continues today, where perfumes are becoming increasingly expensive, with their packaging and brands becoming more symbolic than even the scents themselves.

After Dr. Ally Louks’ PhD, Olfactory Ethics: The Politics of Smell in Modern and Contemporary Prose, went viral online and garnered her absurd amounts of hate, it became clear how little people know about the power perfume has played in social economics throughout history. With the reactions to her paper, I was reminded of Plutarch’s description of Cleopatra’s arrival in Tarsus. Her perfume was used as a tool to establish herself, to signify her social class to others, to seduce Antonius, there was, as Patrick Suskind states in his novel Perfume: A Story of a Murderer, a “persuasive power of odor”.

I thought it would be interesting to analyze fragrances throughout significant era’s of history where perfume was used both to mask ones scent as well as establish their social status. As I did my research, though, I found that so many prominent figures in the world of perfuming were women. So this essay/research-paper/culture-critique, whatever you want to call it, is an exploration of specifically women’s roles in creating the social economics we have today in the world of perfuming.

This is, of course, not a complete chronicle of every significant scent throughout every significant era in history, but I’ve compiled what I think is a good list of the more important or intriguing ones I could find. I also tried to be as specific as I could with the recipes because I think it would be interesting to remake some of these with the modern variations of ingredients and tools we have today.

Tapputti-Belatekallim of Mesopotamian Babylon (c. 1200 BCE)

“When you enter our house in the fragrance of cedar-wood, threshold and throne will kiss your feet. Kings, rulers, and princes will bow down before you; they shall bring you tribute from the mountains and the plain.”

- Epic of Gilgamesh, c. 2000 BCE

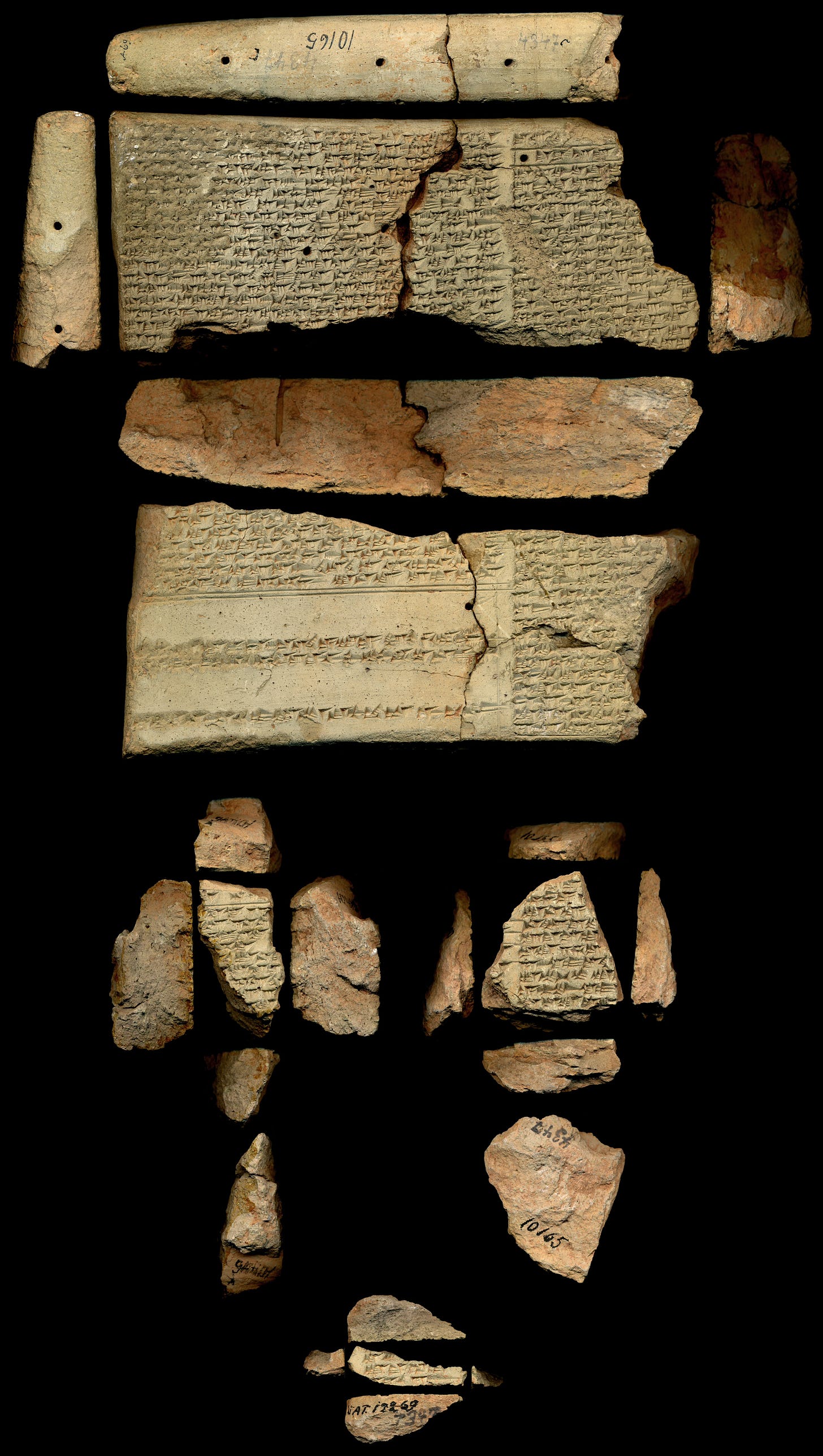

To talk about perfumes, we must, of course, give credit to the most ancient records we have of perfume making. Tapputi, given the title Belatekallim (meaning a female overseer of a palace) is considered the oldest known perfumer (and female chemist!) in history. She was the personal chemist for King Tukulti-Ninurta I of the Assyrian Empire and, since most perfumers of the time were women, it is not her gender that is significant to her work but her contributions to todays world of science. Tapputi, as you’ll see in the tablet below, employed the use of chemistry practices like distillation and solvents to create stronger fragrances.

Throughout history, and especially during the times of the Assyrian Empire, perfumes, oils, and incense were highly coveted and used for a multitude of religious ceremonies as well as for personal use. It distinguished royalty from peasants and signaled ones amount of religious devotion through its use in temples. Because of it’s role in these important ceremonies as well as it’s rare ingredients, perfume became a social standing of its own.

The most ancient and original recipe we have of Tapputi’s it what is able to be transcribed from the fragments of a cuneiform tablet from the ancient library of Aššur. The direct translation of the KAR 220 fragments are, unfortunately, too long and detailed for me to include here, but I would highly recommend checking out the entire translation for yourself. It is so interesting that the use of distillation was an established technique almost 6000 years ago (and probably much earlier)! Though Tapputi is likely not the very first perfumer, her practices have withstanded the test of time and it is her teachings that we have access to today.

Tapputi employed the use of flowers, oils, and calamus, as well as cyperus, myrrh, and balsam to create a strong fragrance. She would mix these aromatics into water or other solvents, distill the mixture to remove particles, and filter the remaining liquid to ensure a pure and strong scent.

This process was by no means a simple or quick task. Tapputi was a precise and detailed perfumer, going as far as to perform certain steps at specific times of the day. The tablet describes how she would do one step of her formula “at dawn, on the rising sun”, leave another step to steep overnight, and then operate at the end of the day or in the evening for other steps.

Through her complicated and time-consuming art of making perfumes, Tapputi contributed to establishing the King as a powerful figure over the ruling class. Her work as a chemist and perfumer was reserved for the elites of the palace, as the tablet specifically described her fragrances as “fit for the king”. The average person did not have the wealth, time, or resources to make these scents or to hire someone else to work tirelessly for them. Through her revolutionary practices, Tapputi was a modern-day chemist, innovating the world of perfuming for future generations.

Cleopatra VII Thea Philopator, Queen of the Ptolemaic Kingdom of Egypt (69-31 BCE)

‘The barge she sat in, like a burnish’d throne, / Burn’d on the water; the poop was beaten gold, / Purple the sails, and so perfumed that / The winds were lovesick with them… / …From the barge, a strange invisible perfume hits the sense…’

- William Shakespeare, Antony and Cleopatra, 1623

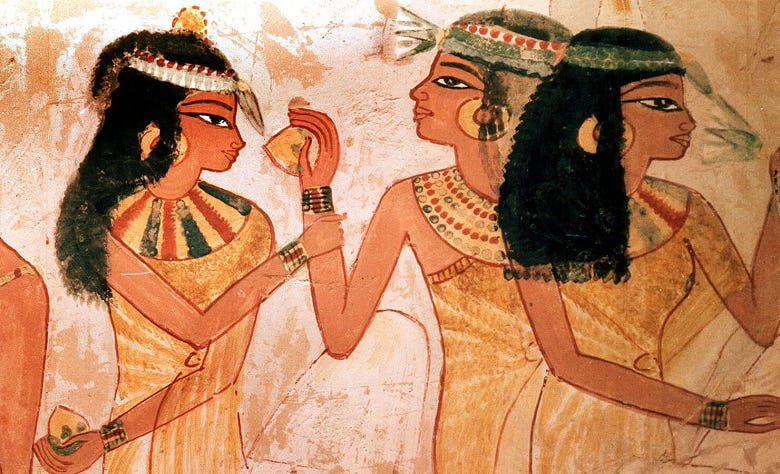

An Egyptian queen whose scent was so alluring that most mention of her in ancient text also mentions her perfume, Cleopatra wielded the power of fragrance to her advantage throughout her life. There is a popular legend that Cleopatra would literally dip her sails in perfume so her scent would waft ashore as she passed by. Though the accuracy of this is questionable (many believe it was an over-exaggeration on Shakespeare’s part), it wouldn’t be completely untrue to believe that the queen would so heavily scent herself and her ships that people would be able to smell it from afar.

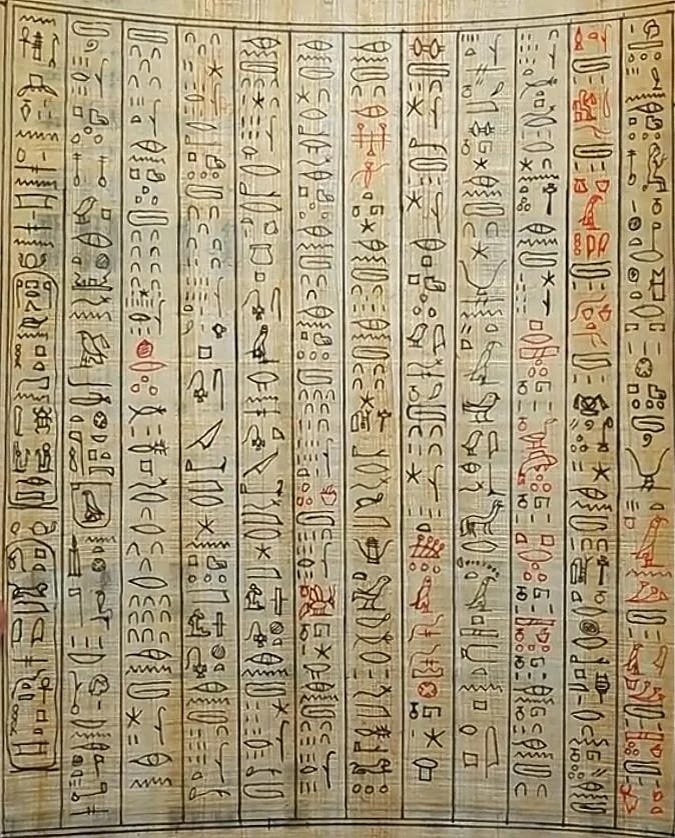

The era of fragrance during the time of Cleopatra found the rising popularity of ‘kyphi’, or kapet, for perfume use. The recipes for kyphi were of such importance that they were inscribed onto walls of the Philae and Edfu temples in Egypt.

Variations of the recipe were sometimes up to 16 ingredients long and involved an elaborate concoction of aroma’s not easily available to the commonwealth. Cleopatra was, through her complicated scents created by her personal perfumer laboratories, establishing a boundary between her and her people. Through her fragrance, she was ensuring people would know, beyond simply her clothing and jewelry, that she had more money, more resources, and more time to be able to smell good.

Galen (129-216 CE) was a Greek physician who studied in Alexandria and, therefore, had access to many Ancient Egyptian texts. In his essay On Antidotes he refers to a scroll written by philosopher Damocrates, in which he discusses his use of a kyphi recipe written by Greek physician Rufus of Ephesus (80-150 CE). His recipe is translated in Lise Manniche’s 1999 book Sacred Luxuries: Fragrance, Aromatherapy, and Cosmetics in Ancient Egypt:

“90g of raisins with skin and pips removed ; ‘a little’ wine ; ‘sufficient’ honey ; 90g ‘burnt resin’ ; 45g ‘nails’ of bdellium ; 45g camel grass ; 33g sweet flag ; 11g pure cyperus grass ; 4g saffron ; 11g spikenard ; 2 ‘semis’ of aspalathos ; 15g cinnamon or cardamon ; 11g good cassia”

Rufus advices that the honey and raisins should first be mashed together, then the bdellium and myrrh should be ground with wine until it is the consistency of “runny honey”. These two mixtures should then be combined. The rest of the ingredients should be seperately ground and added. Lastly, the paste should be formed into pellets to be dried and burnt as incense. To create a perfume oil, these same fragrant ingredients were mixed with olive oil.

This scent was used to purify temples and homes and perfume one’s clothing. Greek physician Dioscorides (c. 100 CE) even claims burning kyphi was used to treat asthma, essentially a modern day aromatherapy! Cleopatra, of course, used it to send a message. She made sure she and her ship smelled so strongly of her perfume that she was practically enchanting the Roman people with her scent.

Along with kyphi, I also wanted to mention another popular perfume likely used by Cleopatra. Mendesian perfume is stated in some legends as the perfume Cleopatra would “soak her sails” in. Paul of Aegina wrote this recipe for the fragrance in his 1847 book Medical Compendium in Seven Books:

“It is made with 10 pounds of oil of balance; 3 ounces each of myrrh and cassia quill; 1 pound of terebinth; 3 ounces cinnamon. This perfume is not boiled; instead, the dry ingredients are added to the oil and stirred for 60 days. Next, after it has been melted in part of the oil, the pine resin is added. Then it is stirred for another 7 days and stored.”

In total, the process for this single perfume is almost 70 days long. That’s over 2 months of a persons time spent brewing this fragrance! What kind of everyday person would have access to 10 pounds of oil and the free time to brew a 70 day long recipe? The answer is, of course, no average person was making this. These recipes, their large quantities of difficult-to-obtain ingredients, and the effort required to make them ensured that only the wealthiest people (or, more likely, their personal perfumers) would be able to make them. When someone walked by on the street, before you even saw them, the scent of this perfume would tell you everything you needed to know about their economic status. Smelling good was a luxury granted only to the ones who could afford it.

Elizabeth of Poland, Queen of Hungary (1305-1380 CE)

“They then took from the basket silver vases of great beauty, some of which were filled with rose water, some with orange water, some with jasmine water, and some with lemon water, which they sprinkled upon them.”

- Giovanni Boccaccio, The Decameron, 1353

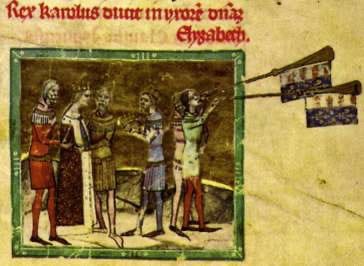

You’ll notice by now the common theme of perfume and innovation in fragrance surrounding royalty, once again attesting to the social economics of scent. The Middle Ages in Europe saw the rise of many floral perfumed waters. Hungary water, or the Queen of Hungary’s Water, was significant as it was one of the first alcohol based perfumes produced in Europe. Though the history surrounding it is disputed at times, some legend attribute the making of this perfume to the Queen Elizabeth, or Isabelle, of Hungary around the end of the 14th century. Some legends says that, in 1370, a hermit or reclusive monk gifted the Queen the recipe for preparing this perfume and, after trying it, the almost-70-year-old Queen became so beautiful that a 20-year-old royal, believing them to be of similar ages, asked her hand in marriage. Other records claim the aging Queen personally requested her court alchemists to produce a tonic that could restore her youthfulness.

Originally, the perfume was prepared by distilling rosemary with aqua vitae. This is assumed to be the first mention of using alcohol to extract essential oil from plants for the use of perfumery in Europe. In his 1697 book A Plain Introduction to the Art of Physick, John Pechey describes the recipe for the fragrance:

“Gather Rosemary Flowers, when they are at their best, and fill a Glass Cucurbit half full with them; pour on them a sufficient quantity of Spirit of Wine, to infuse them ; set the cucurbit in a Bath, and joining its Head and Receiver, lute close the junctures, and give it a digestive Fire for three days ; then unlute them, and pour into the Cucurbit that which has bin distilled; refit your Limbeck, and increase the Fire strong enough to make the Liquor distill drop by drop, and when you have drawn about two thirds of it, put out the Fire ; let the Vessels cool, and unlute them. Keep the Water in a Vial well stopped.”

A more detailed recipe, with specific quantities, is included in the 1779 book A Toilet of Flora:

“Put into an alembic a pound and a half of fresh picked Rosemary Flowers; Penny royal and Marjoram Flowers, of each half a pound; three quarts of good Coniac Brandy; having close stopped the mouth of the alembic to prevent the spirit from evaporating, bury it twenty-eight hours in horse-dung to digest, and distill off the Spirit in a water-bath.”

The same book describes that the Hungary Water can be diluted with Spring Water and taken once or twice a week in the morning, as well as being used to bathe or to ease body aches. The author, French physician Pierre-Joseph Buc’hoz, even claims the recipe can strengthen someone’s sight or “dispel gloominess”. The Queen of Hungary had essentially created a Medieval anti-depressant!

Though the history of the Queen isn’t completely clear, with contrasting accounts of her age and her history of marriages, the amount of mention of this Queen in historical text is likely based on some measure of truth. Since most legends state that the purpose of Hungary Water was related to gifting the aging Queen her youth, that is also the likely reason for making the perfume, reminiscent of the natural anti-aging remedies of our time. It’s interesting to see how women of hundreds of years ago dealt with the same issues that women today deal with in terms of their inescapable aging. That historic women felt the same societal pressures we feel today to maintain our youth and beauty from their young adulthoods to their deaths. Even as the wealthy monarch of a country, Elizabeth of Poland, Queen of Hungary and Regent of Poland, felt desperate to “regain” the beauty of her youth.

Caterina de’ Medici, Queen Consort of France (1519-1589 CE)

“This is about the ornamentation of the graceful ladies, not yet so much about the vestments that she must wear, but the things that a beautiful body requires, and how beauty can be acquired with artifice.”

- Giovanni Marinell, Gli ornamenti delle donne: tratti dalle scritture d'una reina greca per, 1562

While many of the French people may have disliked their new Queen’s attraction to the “Dark Arts”, they could not deny that she smelled good. Catherine de Medici was an Italian noble born into the powerful aristocratic Medici family. During Catherine’s youth in Italy, the country was considered the world’s center of perfumery and, due to her noble status, Catherine had access to many premier fragrances. In addition to her interest in perfumes, Catherine relied heavily on astrology and the prophecies of seers, notably Nostradamus, for much of her reign. Due to apparently strange remedies she practiced in order to bear children, some claims being that she drank the urine of pregnant animals and mixed strange herbs into her food and wine, the French people began to distrust the Queen. It didn’t help that she was unable to bear children for many years, as, even though most historians agree it was likely due to a malformation of the King, the couple’s sterility was attributed to Catherine.

For her marriage to the future King of France, Catherine commissioned Dominican friars of Santa Maria Novella to create a scent for her bridal present. The fragrance was made from Italian citruses, petigrain, neroli, and lavender and described as “fresh and citrusy”. Catherine enjoyed the fragrance so much that she brought Rene de Florentine, a perfumer of Santa Maria Novella, with her to France, in turn also bringing the modern world of perfume to the country’s streets. Florentine set up shop in Paris and soon began crafting scents that would establish France as the world’s prominent perfume-makers.

Catherine introduced many fragrant inventions to the French nobility. She brought scented gloves from Tuscany, made to mask the smell of poorly-tanned leather, and pomanders, pendants filled with perfume, that her and her entourage would wear around their necks. Catherine, though distrusted by some for her apparent interest in magic, was regaled by French nobility for her introduction of the art of fragrance to their court.

The scent created for the Queen by Santa Maria Novella, called Acqua della Regina, is well-known and still available today, so I thought I would instead focus on lesser known perfumes made during the same period and likely inspired by Catherine’s perfumery.

In Giovanni Marinell’s 1562 book Gli ornamenti delle donne: tratti dalle scritture d'una reina greca per, or The Ornaments of Women, he describes a multitude of beautification processes for women of the time. One perfume recipe of his that I felt best encapsulated the preferred citrus scent of Catherine’s was one consisting of “lavender, elderflower, mint, lemon balm, citron, and cloves blended with musk in a rose water and made of a alcohol base”. He described this scent as “fresh flowery and oriental”.

From Marinelli’s own words, the power of a fragrance wasn’t simply to smell good, it was the mark of a “beautiful body”. Through expensive and rare perfumes crafted by only the best perfumers, royals ensured that they were in control of the world of perfumes. The lower classes wouldn’t be able to recreate their recipes even if they tried, as they likely couldn’t afford the ingredients. In today’s world, we continue to have our Catherine de Medici’s and Rene de Florentine’s. Large, well-established companies creating unattainable scents from unique, and sometimes strange, aromas catering for their small, high-class clientele. The everyday person can only dream of affording some of the absurdly priced perfumes on the market today.

Dr. Louks wrote in her controversial PhD that “smell very often invokes identity in a way that signifies an individual’s worth and status in an inarguable manner that short-circuits conscious reflection”. I like to think Cleopatra had this same thought as she sailed to Tarsus and mused over how she would captivate the Roman people. Or what Catherine de Medici thought as she pondered over how she would appeal herself to people who distrusted her and her strange practices.

Through my research, I found many hidden female figures in history that had such a significant impact on the world of perfuming. I did as much research as I could to find original, historic accounts of these women, but the passage of time will, unfortunately, always hinder the quest for information. I can’t imagine the amount of cuneiform tablets containing Tapputi’s other recipes that we will never access; or the recipes used by Rene de Florentine that were of such importance to the Queen that she apparently had secret passages for her perfumers.

Additionally, I am aware that there is a large focus on European perfume practices in this post. The East was extremely signifiant for the world of perfume, much of the trade in Ancient China was of fragrant incense, and Medieval Islamic aromatherapy for both medicinal and perfume use is heavily documented. Iranians are actually considered the first perfume manufacturers and cultivated many fragrances from rose water! Unfortunately, I simply couldn’t find specific women involved in impacting perfume at the time in those areas. I want to make sure any information I included was supported by multiple sources, so I wasn’t able to focus on the Eastern world due to lack of significant documentation on female perfumers. If I find any information in the future, or if you guys know any and would like to share, maybe I’ll do another paper with a focus on perfumers in the East!

So many ancient perfume recipes employed ingredients and processes that perfumers still use today. It’s such an amazing testament to the impact of these chemists and their ingenious formulas that we’re still inspired by them almost 6000 years later. Similarly, we continue their practice of using perfume to assert one’s greater social status over others. Just like royalty of the past, perfume brands today spend millions of dollars on rare perfume scents packaged in crystal bottles and promoted by famous brand ambassadors. The ideas of Dr. Louks’ PhD extend far beyond simply literature or hypotheticals, they are relevant to the every-day world around us, just like they were for Cleopatra 2000 years ago and Tapputi 6000 years ago or even the ancient royal perfumers before her who left no trace of their revolutionary work.

Thank you so much for reading! I had a lot of fun doing this deep-dive into ancient perfumes and I hope this was interesting to anybody as obsessed with niche history as I am! Perfumes today can be so absurdly expensive, so I think it would be interesting to start experimenting with making our own scents inspired by some ancient recipes. It would definitely give a new name to the concept of a “signature scent”.

I would love to hear any thoughts or comments that you guys have about anything I included in here! Also, I did as much research as I could to ensure everything was accurate, but if there’s something here you believe is incorrect, please let me know so I can fix it! Thank again and I’ll see you guys soon <3

Thank you! I subscribed instantly! I love exploring the past even though through tiny fragments and bits we can still find today. Destroying the ancient texts was and is humanity's most awful crime!

Thank you for doing the great work! 💕

I love this so much 🌹