Stop begging the police to join your revolution

The issue at the heart of the No Kings movement

Power concedes nothing without demand. It never did and it never will.”

—Frederick Douglas

Last weekend, tens of thousands gathered for the No Kings protests as a coordinated, nationwide demonstration against authoritarianism. Organized to coincide with Donald Trump’s birthday and the United States military’s 250-year parade, the protests targeted what organizers described as the ongoing consolidation of executive power and violence.

But at their attendee debrief call on Monday, the No Kings strategy wasn’t about breaking free from those institutions. It was about convincing them to switch sides.

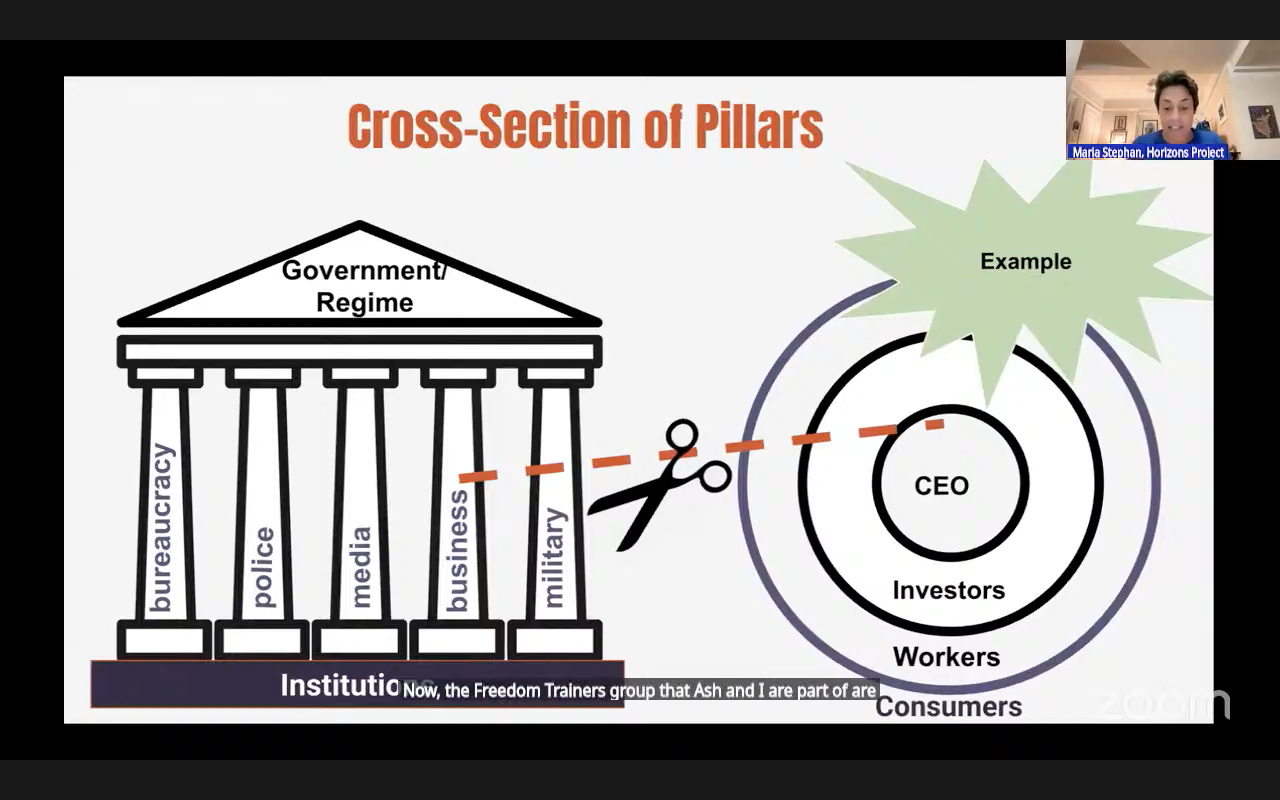

In the call, Maria Stephan of the Horizons Project laid out the movement’s “theory of change in this moment of authoritarianism”. Stephan described how the movement’s purpose was to target the “pillars of authoritarian regimes”—civil service, police, media, business, military.

But their goal is not dismantlement of these pillars, but “to pull them away from supporting authoritarian regimes and towards supporting our pro-democracy movement.”

These are the organizations and institutions that provide autocrats with the social, political, and economic power they need to wield control…we need to get these pillars to stop complying with authoritarian regimes.

[…]these pillars are not monolithic. They are made up of people with different identities, interests, and loyalties…Are they actively or passively supporting authoritarian practices? Are they on the fence? Are they on our side? Understanding this is key to designing campaigns whose goal it is to shift their incentives.

Central to the No Kings approach is the liberal belief in individual conversion. They think that by winning over people inside these systems, the system itself will change.

This idea treats these pillars like passive, apolitical architecture that can be chipped away at or persuaded to bend in the “right” direction. In reality, these pillars are not merely holding up authoritarianism, but actively shaping and reproducing it.

Civil service doesn’t simply carry out orders, it builds the bureaucratic infrastructure that sustains repression—from immigration raids to protest permitting. The media platforms fascist rhetoric and rebrands police killings as “officer-involved incident”. Businesses, like Amazon, fund both sides of conflicts by contracting with ICE and police departments while sponsoring Pride parades and diversity initiatives. They are systems that reproduce power, regardless of the individuals within them.

This is especially true of the police and military. These aren’t just groups of people with differing opinions, they are systems with a specific logic and function. Their job is to manage, contain, and violently suppress threats to the status quo. They do not serve in authoritarian regimes “despite” their internal diversity, they are the regimes most reliable tools because they are inherently structured to override individual conscience.

So when the No Kings organizers talk about loyalty shifts, it raises the questions: What happens when individual values conflict with institutional purpose? Can you really “turn” an authoritarian tool into a democratic one simply by convincing enough individuals within it to “see the light”?

Their stated tools for winning pro-democracy campaigns are: “Expanding the repertoire of nonviolent tactics”, “Elicit loyalty shifts among key pillars”, and “Maintain discipline and make repression backfire.”

But reality doesn’t offer much proof of the effectiveness of these tools. Black officers integrated into racist police forces don’t neutralize police brutality. Progressive politicians in police unions haven’t changed the systems that protect officers from accountability or the policies that reward aggressive policing. Even media outlets that pride themselves on democratic ideals have platformed fascist rhetoric and laundered authoritarian violence into the language of law and order.

No Kings organizers say research shows “that basic organizing and outreach to members of these pillars is key to getting them to shift their loyalties.”

But appealing to their loyalty misunderstands their inherent purpose.

There is a liberal fantasy that power can be reasoned with instead of resisted. That everyone, given the right appeal, might eventually “come around”. Where the Nuremberg defense tried to humanize perpetrators who were “just following orders”, this flips the logic by suggesting that as long as someone inside a system has doubts, the system itself must still be redeemable. But the result is the same: accountability is deferred and systems remain untouched.

You can see these beliefs reflected in the rules of the protests themselves. Attendees were told to stay calm, not provoke, treat the police as neutral or even potentially sympathetic. There is an absence of any language that directly challenges law enforcement or the military as institutions. Even concerns about surveillance or repression were suppressed because they didn’t fit the tone of polite and palatable protest.

In the meeting, Stephan said:

Being able to bring about loyalty shifts and defections in key pillars of support and being able to maintain discipline in the face of provocations, violence, and repression and making that repression backfire is key to success.

Under these beliefs, discipline doesn’t just mean organized action. It means staying within the bounds of what authority finds acceptable. It means choosing language and tactics that wouldn’t offend the very institutions they claim to be resisting.

This liberal restraint isn’t limited to the U.S. In Toronto, organizers softened the protest’s original theme. They changed “No Kings” to “No Tyrants” to avoid offending monarchical sensibilities in Canada, and swapped “No Crowns” for “No Clowns”. They encouraged attendees to dress like Trump or “one of his cronies”.

Rather than confronting structural power, the protest was reframed as spectacle. Their call to “de-escalate any potential confrontation” echoes their goals of not simply peace, but appeasing. Even abroad, the movement seems more interested in being digestible than in being dangerous.

What does it mean to fight authoritarianism while being bound to the language of the state?

There have also been reservations about the organizational engine behind No Kings, the 50501 movement. Meaning “50 Protests in 50 States, 1 Movement”, 50501 was launched as a mobilization against authoritarianism. Their goal is to promote coordinated, peaceful demonstrations across the U.S. and abroad.

But critics have raised concerns about the movements tactics and affiliations. Its ties to institutions like Democrats Abroad and Walmart heiress Christy Walton have led to accusations that the movement isn’t actually challenging authoritarianism so much as creating a sanitized, elite-approved version of resistance.

At the nationwide April 5 “Hands Off” protests, 50501 organizers were criticized for their sanitized rules. They told protestors to “call the cops if you see a counter-protestor” and that they could not stand on the steps of City Hall unless they were “certified media”, with a press pass or some journalist credential.

There is also consistent critique from the 50501’s cozy relationship with the police. Across multiple cities, organizers have not only coordinated closely with local police departments, but have allegedly even called the police on protestors at their own events.

Even in spaces meant to critique state power, there is an ideological comfort with policing as a legitimate force.

In the meeting, as well as on their official website, No Kings cites the 3.5% principle as a central aim. “We’re inspired by the 3.5% principle”, organizers said, “it only takes 3.5% of the population engaging in sustained, strategic protest against authoritarianism to achieve significant political change.”

However, the historical frameworks the movement draws from face limitations when applied to the United States. The 3.5% principle comes from scholars Erica Chenoweth and Maria Stephan, who studied how small, committed movements could bring down authoritarian regimes through nonviolent resistance.

But those movements weren’t trying to reform their corrupt institutions. They were actively trying to overthrow them. Chenoweth’s research draws from dozens of nonviolent uprisings, including the People Power Revolution in the Philippines, the Serbian student-led movement Otpor! and the protests that ended Chile’s dictatorship. In each of these cases, mass mobilization wasn’t about tweaking authoritarian structures, it was about completely tearing them down. Their strategy wasn’t to convert the police or military, but to apply enough public pressure that the regime lost its ability to function. And many of these regimes were structurally vulnerable, with their legitimacy already collapsing, both domestically and abroad.

Trying to apply those same tactics to the U.S. presumes that we are in the same position as these movements. That we are living under a recently corrupted system and that our job is to restore it to its former democratic glory.

So what does it mean the “shift loyalties” back to democracy in a country built on slavery, indigenous genocide, and imperial conquest? What does it mean to try to recruit institutions like the police, who have always existed to enforce these foundational violences, into a project of liberation?

These goals are founded on the nostalgic myth that America was once a “perfect democracy”. One that’s not entirely unlike “Make American Great Again”. Both sentiments mask the reality that the United States has always been authoritarian at its roots. And that meaningful change requires acknowledging that history, not just longing for a idealized past.

I feel the issue isn’t that we’re being “too radical”, but that we’re not dreaming big enough. The vision put forward by the No Kings organizers still orbits around the approval of power. It still imagines progress as something that requires buy-in from the police, from the military, from the very institutions designed to contain us. But do we need their loyalty? Do we need them to exist at all?

While No Kings and 50501 invest energy into courting police and military loyalties, other groups reject this entirely. Organizations like Remembrance Project and Defund Advocates center abolitionist principles, insisting that policing and militarism cannot be reformed or repurposed so they must be dismantled. Their critiques cut through the fantasy of “loyalty shifts” and demands structural transformation, not polite persuasion.

Abolitionist thinkers like Mariame Kaba and Ruth Wilson Gilmore don’t waste time wondering how to make policing kinder or military force more democratic. They start from the understanding that these institutions are not broken, they are operating exactly as they were built to. And so their goal isn’t to fix them, but to outgrow them. Kaba writes that abolition isn’t just about absence of prison or police, but about presence. About building systems rooted in care, accountability, and collective safety. They call for “changing everything”, because these thinkers understand that everything—from housing, to health, to food, to education, to land—is connected under an authoritarian regime.

In practice, this means protest and organizing work that centers mutual aid, community defense, transformative justice, and a refusal to cooperate with prison systems. Even when doing so risks state repression. Rather than trying to appeal to police for protection, abolitionist organizers train in de-escalation, rely on community medics, and build coalitions that treat care as the foundation of safety.

These protests might not have press-friendly demonstrations. They might not look disciplined in the traditional sense. But they would be rooted in the knowledge that the people who build the world will be the ones to remake, not the ones paid to protect it as it is. A protest like that wouldn’t ask the police to join them. It would ask who we could become without them.

I think that trying to “recruit” the very institutions who hold up authoritarianism shows that our future must to be negotiated with those who hold the guns. That democracy, whatever version we’re trying to build, won’t be legitimate unless our jailer approves. It is a naive framework that promises change without risk.

But freedom isn’t something granted, it is something that must be seized.

Reforms only make police polite managers of inequality. Abolition makes police and inequality obsolete.

—Derecka Purnell, “Becoming Abolitionists”

This is the sort of vague, doomtastic argument which could also be used to prove that the US was fascist under Obama