In the winter of 1965, three days before the assassination of Malcom X and six months before the Voting Rights Act was passed, the Cambridge Union Debating Chamber was packed to over-capacity. 700 students and guests filled the grand chamber, hundreds of others packed into adjacent galleries for a live broadcast, and even more stood waiting outside, hoping for a chance to get in. Over 1000 people were there to witness what has since become known as one of the most influential intellectual debates on race in America.

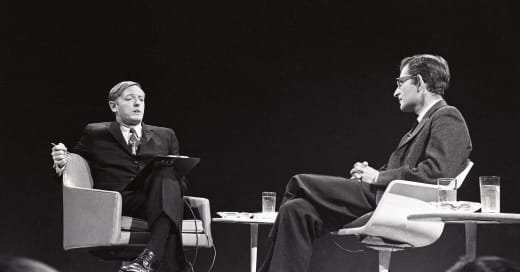

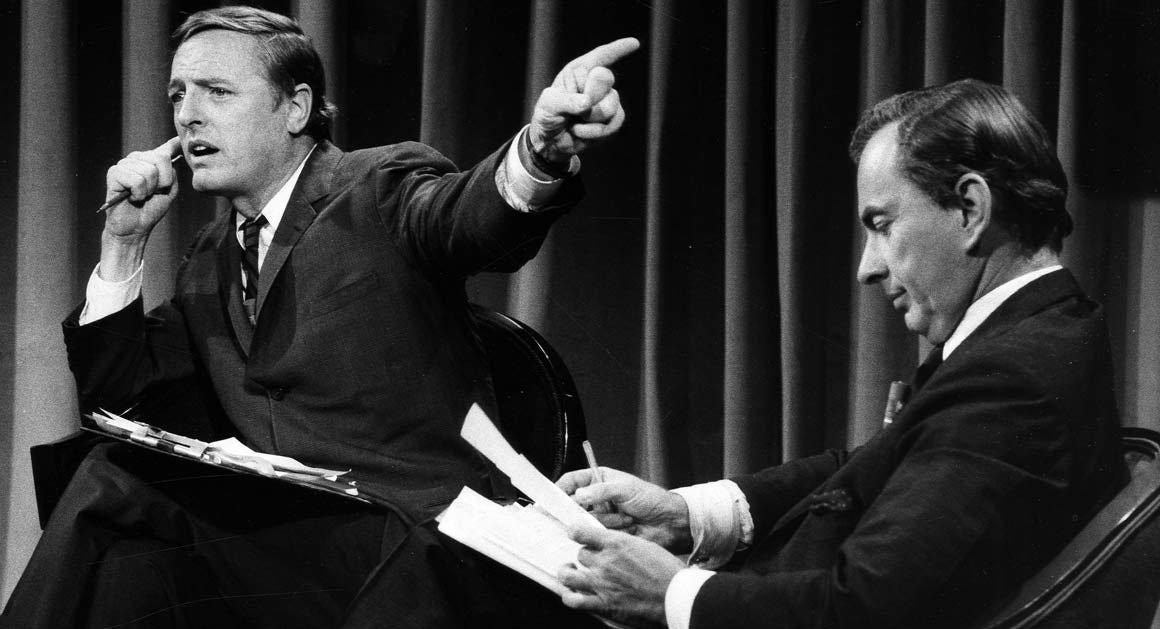

That night, James Baldwin and William F. Buckley Jr. stood on opposing sides of the question: “Has the American Dream been achieved at the expense of African Americans?”. It was an electrifying debate, with the two men embodying not just opposing arguments, but opposing Americas. Buckley, a conservative commentator, argued that personal responsibility, not systemic oppression, determined ones success in the country. While Baldwin, a civil rights activist carrying the weight of the lived experiences of a black man in America, spoke on the country’s foundations of racial injustice.

“I picked the cotton and I carried it to market and I built the railroads under someone else’s whip.”

The weight of his words was felt throughout the hall, those who had entered certain in their convictions felt their opinions begin to unravel. When it came time to cast their vote, the audience—composed mainly of British conservatives, many from the upper echelons of society—decided on an overwhelming result: 540 to 160 in favor of Baldwin. Even those predisposed to Buckley’s views could not deny the force of Baldwin’s argument. That was the ability and purpose of the public intellectual—to challenge deeply held beliefs, to present ideas so undeniable that they could break through even the most firm ideologies.

The significance of the debate extended far beyond the wooden walls of the chamber. It was re-broadcasted by several American stations, dissected in newspapers and classrooms, and continues to maintain relevance even today. The debate was a moment that reflected how intellectuals at the time were more than just thinkers, they were shapers of cultural discourse and influencers of entire societies. It represented an era when public intellectuals had real power to shift public mindsets, to educate, and to challenge.

It’s difficult to imagine such a debate commanding that kind of attention today, especially not with the same level of cultural impact. Where once a thousand people crammed into a hall to listen to debates, today’s intellectual confrontations unfold through the online sphere. What once demanded silence and focus now competes with the endless scroll of content. This shift from intellectualism to spectacle marks a fundamental change in the way our culture engages with ideas.

But, first, who is the public intellectual?

The term “public intellectual” was first used by Russell Jacoby in his The Last Intellectuals: American Culture in the Age of Academe. He defined them as “writers and thinkers who address a general and educated audience”. Public intellectuals used their knowledge and intellectual authority to address social, political, and cultural issues to the public. It was especially important for them to use their platforms to challenge the status quo of the time.

Baldwin’s writing on race and identity, Sontag’s work on art and culture, and Chomsky’s critiques of U.S. foreign policy contributed to larger societal conversations. They weren’t confined to scholarly circles, but directly engaging with a wide audience through media. Public intellectuals were invited onto television programs, debated on national stages, and were the subjects of countless news articles and features.

In essence, the public intellectual was a rare embodiment of both intellectual depth and cultural visibility, making them important cultural forces of their time.

Today, though, these kinds of figures are becoming increasingly rare. The role of the public intellectual has become fragmented, the term now difficult to define. But what forces led to this decline and what has taken their place? If public intellectuals once guided discourse through their writing, lectures, and debates, who—or what—has replaced them?

Always at the scene of the crime—the Internet

The first thing to recognize is that the Internet radically changed everything. Public intellectuals of the 60s, 70s, and 80s thrived in a media landscape that was relatively limited. Their voices stood out against the noise in a time where there were fewer television networks, newspaper publications, and much less intellectual gatekeeping. Intellectuals debated politics on live television, had their essays printed in reputable publications, and reached a range of audiences through books and interviews. In this environment, public intellectuals became cultural fixtures.

Today, the intellectual sphere feels fragmented, if not entirely sidelined. The kind of person who would have once been a Chomsky or Baudrillard now has to fight for attention in a media landscape that rewards speed and virality over depth and nuance. Thinkers today aren’t household names, but niche micro-celebrities fighting for engagement on platforms where even the smartest ideas risk being reduced to viral headlines.

The sheer volume of voices has also made it difficult to gain any sense of intellectual authority. What used to be a position held by a select few is now fractured into a thousand voices, each with a different opinion on the latest trend or crisis. With social media platforms as our primary source of cultural consumption, intellectualism has shifted from being a deliberate, slow-moving art to a constantly churning, attention-seeking industry.

Public intellectuals aren’t becoming difficult to find because we’re in any kind of deficit of brilliant thinkers, but because the space for these figures has nearly disappeared. Intellectual influencer’s today—though brilliant in their own right—have to contend with branding themselves for social media. They have to publish articles and make content that generate engagement rather than encourage deep thought. The complexity and weight of ideas is often sacrificed for the sake of appealing to the masses.

“…intellectuals are not professionals denatured by their fawning service to an extremely flawed power, but—to repeat—are intellectuals with an alternative and more principled stand that enables them in effect to speak the truth to power.”

— Edward W. Said, Representations of the Intellectual

When your goal is not only to present ideas but to make them palatable and digestible for a distracted audience, the boundaries of intellectualism start to blur. Ideas are no longer for discussion, they’re for consumption.

Public intellectuals wrote so influencers could aestheticize

Meanwhile, the people who do shape culture—the ones who influence what we wear, how we speak, and even how we think—are no longer intellectuals, but influencers. And while this may feel like the natural evolution of celebrities, it says something significant about what we value today. We no longer look to those who challenge us intellectually, we look to those who offer us a perfectly packaged lifestyle.

The figures who shape culture operate in an entirely different space today. Someone like Hailey Bieber now dictates trends through the silent language of aesthetics. Her influence, though drastically different from Sontag’s, is no less powerful; but, unlike Sontag, who shaped public thought through her writing and thinking, Bieber’s impact is entirely visual. Every time she debuts a new (strangely food-themed?) beauty trend—’glazed donut skin’, ‘brownie lips’, ‘strawberry makeup’, and, my personal favorite absurdly named, ‘cinnamon cookie butter hair’—it ripples through our culture with a speed and force rivaling the sharpest cultural critics.

Kim Kardashian has arguably done more to shape modern femininity than any feminist writer in the past couple of decades. Her impact on beauty standards and the way we present ourselves online is immeasurable. The Kardashian aesthetic—their curated hyper-femininity and surgically perfected bodies—have become the blueprint for modern beauty. And while one could argue that Kim is an intellectual force in her own right for mastering the art of self-marketing, her influence is entirely aesthetic. She doesn’t make us think, she makes us aspire.

This is what is at the core of this shift. Where public intellectuals once shaped cultural discourse by challenging ideas, most influential figures today shape culture by modeling a lifestyle. The Kardashians and the endless legion of influencers who dictate internet micro-trends don’t engage in public debate or articulate their philosophies in essays and lectures. Instead, their ideas are embedded in the lives they project. Their impact is absorbed passively, not through engagement, but by constant exposure.

This is not an incidental shift, but a reflection of our broader cultural transformation. If Sontag represented a time when public intellectualism had mass appeal, these influencers represent what has replaced it: public aestheticism. A philosopher might spend years constructing a critique on our society, but an influencer can change peoples worldviews with a single Instagram post. Our cultural leaders today embody desire—they are the product, the message, and the marketing strategy all at once.

Even figures with a platform one would consider intellectual, like a podcast or blog, tend to operate within a different framework than the public intellectuals of the past. The most successful are the ones who know how to package their ideas into easily consumable formats. Their content may demand engagement, but not necessarily deeper thinking. The most successful cultural critics of our digital age are simply a different kind of influencer, one who may sell a worldview rather than a skincare routine, but are selling something nonetheless.

Debate is dead, long live discourse

One of the most striking changes in the cultural landscape is how intellectual debates have become increasingly siloed. The grand public discussions of the past have been replaced with subtweets and algorithm-driven echo chambers. Instead of televised debates where intellectuals engage in ideological battles, we have discourse that is either too online to be taken seriously or too sanitized to be relevant.

In the past, intellectual debates were cultural events that shaped public thought. They weren’t just for entertainment, but opportunities for deep intellectual discussions to take place. The debates between William F. Buckley Jr. and Gore Vidal at the 1968 National Convention’s, though infamous for their personal insults and heated exchanges, still reflect the intellectual and ideological sphere at the time. While the debates often strayed from true substance, it captured the public’s attention and had a lasting impact on political discourse.

Intellectual debates like these captured the idealogical zeitgeist of their time, shaping public conversation by engaging their audience with questions on morality, politics, and society. In that time, intellectual ideas reached far beyond the walls of academia.

Today, however, intellectual debates have been fragmented by algorithms, intellectual bubbles, and digital pile-ons. Algorithm-driven echo chambers ensure that we only ever hear from people we already agree with. It’s not that people don’t argue anymore—we argue constantly—but the nature of the debate has changed. The goal is no longer to explore or challenge ideas, but to perform intelligence and “win” whatever discourse is currently relevant. The effect is an intellectual landscape where genuine debate is rare, with ideas either diluted for mass appeal or radicalized within specific groups.

Jordan Peterson has gained prominence less through rigorous academic debate and more through his positioning within broader culture wars. Ben Shapiro has transformed debate into entertainment, where humiliating ones opponent has become more valuable than exploring the complexity of the issues at hand. Debate has become less about the pursuit of truth and more about performing intelligence for an audience.

Academia’s paywalled ivory towers

But the death of the public intellectual isn’t just because of the changing media landscape, it’s also a result of the way access to knowledge itself has changed. There was a time when intellectuals were expected to be generalists, able to move between literature, politics, science and philosophy to make them more accessible to the average person. Sontag or Russell weren’t confined to one narrow field, they engaged with a range of complex ideas to make them digestible and thought-provoking for the public. Today, however, intellectual life is more rigid.

“Academic life has become more professionalised. They write for each other, not for the general reader. Academic political philosophy today, for example, has zero influence on the practice of politics. I doubt now whether any politician could name a leading academic philosopher. No one would know who they were.”

— John Gray

Excessive intellectual specialization has transformed the academic world into a closed-off echo-chamber, where scholars speak only to their peers rather than engage with the public. Where once public intellectuals acted as bridges between specialized knowledge and mainstream discourse, today’s intellectuals are confined to academic circles. Philosophers today aren’t expected to comment on literature or politics the way Sartre once did, but to produce work for a handful of their peers in their intellectual niche.

Even when today’s intellectuals do attempt to step outside of their academic niche, their knowledge is often questioned because of the very nature of specialization. A historian writing on politics or a physicist dissecting philosophy might be met with skepticism because intellectual authority is tightly policed within rigid boundaries.

The bridge between academia and public life has been eroded. Our intellectuals today are stifled by institutions that demand more and more specialization in a specific area, making their work increasingly unavailable to the general public. Meanwhile, mainstream conversation continues to move further away from intellectualism entirely. Dominant media platforms prefer fleeting distractions and sensationalized headlines rather than a space to prioritize substance and intellectual discussion.

“Universal access to knowledge must then remain the pillar supporting the transition toward knowledge societies. Whatever the extent and nature of public domain information and knowledge, it is paramount to ensure that content is really accessible to all, without discrimination.”

— Abdul Waheed Khan, former Assistant Director-General for Communication and Information of UNESCO, in Universal Access to Knowledge as a Global Public Good (2009)

Public intellectuals were simply translators, people who helped turn complex ideas into mainstream discussion. But now, intellectuals are trapped producing work for journals and conferences rather than the public sphere. As a result, public-centered intellectualism has become rare. It’s not because intellectuals of that caliber no longer exist, but that the structures that once made their ideas visible have been buried under layers of institutional gatekeeping.

The fear of performing after the curtains been called

It’s also understandable that some hesitate to step into the intellectual sphere today because it feels like everything has already been said and done. We live in a time where every thought, argument, counterargument, and counter-counterargument have already been made and analyzed. The modern landscape isn’t necessarily devoid of intellectuals, it’s that fewer people are willing to step into the role of a public intellectual because they feel that originality is no longer possible.

There’s a frustration in feeling like every idea has already been picked apart by someone smarter, faster, and with a larger audience than you. For many, the impulse to add to the conversation is suffocated by their fear of redundancy. I’m sure a lot of us can relate to that—I know every time I go to write an essay, I feel like I’m just echoing ideas that have already been said before. Even when writing this essay, I’m aware that my discussion isn’t entirely new or unique, which hinders my confidence in writing and publishing it. ‘Why should I write an essay on the death of public intellectualism when someone has already written the essay on the topic?’ ‘Why attempt to challenge the status quo when someone has already been through the cycle of acceptance, backlash, and inevitable irrelevance?’

The result of this thinking? An intellectual echo chamber. Instead of engaging in public discourse, many passively consume content, convinced that someone else has already done all the work and said everything that needs to be said.

But, the truth is, no conversation is ever truly over. History has shown us that ideas and beliefs are never static, they’re shaped by their context and the people who engage with them. The same philosophical questions debated centuries ago continue to evolve and take new meanings as the world changes. The way people understood feminism in the 70s is not the same way we understand it now. The was Baudrillard wrote about media and hyperreality in the 80s is eerily relevant now, but our interpretation of it is shaped by our current digital age. Every era reinterprets the past and every voice adds something new.

The real danger lies in silence. Our belief that everything has already been said has become a self-fulfilling prophecy, where people are discouraged from speaking out at all. But the intellectual space isn’t sustained by a handful of once-in-a-lifetime thinkers, it relies on continuous conversation. No one person can say it all and no one idea is ever truly complete. The question isn’t whether something has already been said before, it’s whether it’s been said by you, right now, in this very moment.

A tragedy or just the evolution of thought?

So, does the decline of the public intellectual matter? Maybe not. Maybe we were always going to reach a point where images spoke louder than words, where aesthetics were more effective than analysis. Maybe this is just the natural evolution of influence in a hyper-visual, algorithm-driven age.

But there is something unsettling about the fact that we no longer expect our prominent cultural figures to challenge us intellectually. We don’t expect them to write, to debate, or shape public discourse in any meaningful way. We just expect them to look good doing whatever it is they do.

The shift from intellectuals to influencers affects how we engage with ideas and decide what really matters to us. If the answer to “who shapes culture now?” is “whoever has the best skin”, then maybe we’ve lost something along the way.

So, can the intellectual space be reclaimed, or has it been permanently absorbed into digital spectacle? Long-form discussions found in podcasts, essays, forums, and other online spaces are a great staring points. Platforms of these media types allow for deeper exploration of ideas, where nuance and depth are greatly valued.

But intellectual spaces aren’t only limited to these traditional platforms. Niche online communities like Internet book clubs or Substack newsletters create new ways for people to connect with unique ideas. You can also incorporate intellectual conversation into your everyday life. Attend local events, art galleries, or even start casual discussions among friends to make these topics more accessible and relevant. The intellectual sphere may have shifted, but it isn’t gone. We simply have to work to reclaim these spaces with people who are willing to engage deeply with ideas.

Ultimately, the death of the public intellectual may not be as tragic as it seems, it may just mean that intellectualism is taking on new forms. But we have to ensure we’re not losing sight of what really matters—the depth, complexity, and refusal to settle for easy answers in the pursuit of something greater.

"Debate has become less about the pursuit of truth and more about performing intelligence for an audience" I think Jubilee is another good example of this. While it tries to "connect" ordinary people with opposing views on numerous matters, it mostly searches for an emotional reaction by the participants and the audience. This is only enhanced by clips of the debates which are also posted on other apps, where it has become normal to cyberbully whoever you don't agree with.

There're plenty of other things that could be criticised about Jubilee, but I just wanted to share that little observation. Loved your post!

Lovely writing! Yes, as someone who thinks of themselves as an academic who wants to pursue the public intellectual, the fear is that I am just saying what everyone is saying. But there is hope. My friends and I are starting a group focused on writing and intellectual debates. We hope to start something that questions our current culture and delves deep into academic literature as well as the cultural landscape. I think it’s important to still have conversations because without them, we will regress (which is something we are seeing). Again, I loved this piece. I’m going to share out with my friends.