What cannot be said only once

beauty—and perhaps understanding itself—depends on saying more than is strictly necessary

In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God.

As machines continue to adapt, and the apparent future in which artificial intelligence will be solely in charge of all creation of art looms, I feel it’s important to return to the fundamentals of what it really means to create something.

I’m sure we’ve all had moments in which we read something online and are so completely sure that a human did not write this. But we’re also not quite sure what it is about it that isn’t right. And in my musings on trying to explain to others what makes AI creations so strange, I have found an appreciation for — a love for — redundancy.

Repetition is often mistaken for waste. The naive efficiency-seeker — the optimizer — believes that anything repeated is evidence of failure. A process performed twice should be collapsed into once. A phrase said again must be tightened. Redundancy calls to mind tedious work, drudgery, the dullness of doing today what you already did yesterday and the day before. But, as with so many things in the modern age, what seems unnecessary to machines often turns out to be indispensable for us humans.

In the 1940s, Claude Shannon said that about half of the printed English language is redundant. You can read “the qu__n wore a cr_wn” and know it says “queen” and “crown.” The predictable patterns of our language let us fill in the gaps. To Shannon, this redundancy was inefficient in his world of telephone wires and telegraph systems, but he also understood it to be essential for human recovery and prediction.

When two AI language models are tasked with inventing their own language, they begin as we all do: with the familiar inefficiencies of human speech. One asks: “There is a girl wearing a red hood. Do you know her task?”. “Tell me what the task is,” replied the other. “She is delivering food and must travel through the forest. Is there danger?”. Thirty-two words to establish this simple scenario.

But because the human language is filled with sloppy redundancies and duplications, the machine optimizes. The exchanges are condensed: “Girl, red hood, task set?” “Task tell.” “Deliver food, path forest, danger?” Which becomes: “Torna, reda-clok, feln-zar?” “Feln.” “Mura-ket, lora-tharn, vektu?” We know that this new language is formed only from the skeleton of the original sentences, from thirty-two words to twelve to seven. The machine language contains only exactly what it needs to convey its message.

Would both hair and hare exist if an artificial intelligence built on optimization and stream-lining could collapse one into the other to avoid confusion? Would it tolerate the dual lead — to guide — and lead — the metal — when a single, unambiguous word would do the job more cleanly?

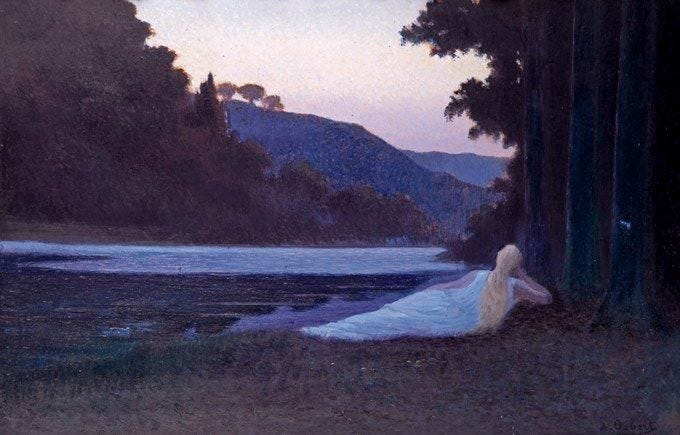

Nature is one of the greatest teachers of repetition. Even though the sun rises and sets every single day, in the same place in the sky as the day before, we still find ourselves enchanted by it. Albums in your camera roll dedicated to the same sky you see every day, pictures posted to your social media of the same sunset everyone else is also seeing. The seasons similarly return to us with redundancy. The same blossoms you saw last year, the same leaves turning and falling. One would assume that this sameness would dull our sense of wonder, but, interestingly, the opposite is true. The peach that tastes familiar is somehow sweeter than the one tasted for the first time last season. Familiarity is what grounds our delight. Pleasure is not only in novelty but in recurrence.

In sameness, our brains find comfort. Evolutionarily, the brain has coded certain familiar things as “safe,” and unfamiliar things as “dangerous.” Our interest is held specifically because nature is both coherent enough to feel safe and minutely varied enough to sustain our attention. It’s why we keep looking at the same sunset. The return is what deepens our attention, and those small differences within the return are what make it worth seeing every time.

Redundancy is one of our oldest artistic instincts, though I feel we rarely name it as such. It solves a fundamental human problem: our reality is too dense to grasp in one fell swoop. Our perception, especially, is pretty lousy. We miss a lot of things at first, we misread lines, and absorb meaning slowly, unevenly. So our art has evolved to accommodate these innately human limitations.

Music, especially, is the one form of art where redundancy is not only tolerated but expected. Repetition is considered to be one of the few near-universal features of music. Loop almost anything often enough — random noise from the environment, a simple spoken phrase — and the brain starts to hear it as song rather than mere sound. Repeated patterns teach us what to expect, and it is only once that expectation is in place can surprise or resolution mean anything at all.

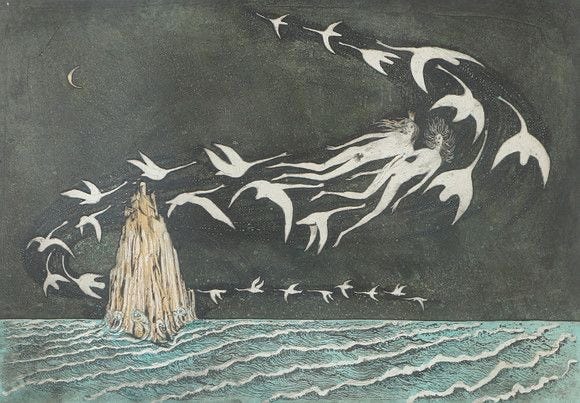

Repetition in visual art has its own importance that surpasses medium. Art is regarded by many as a privileged site of repetition. The same motif or text reappearing in a new time and context becomes something else entirely — the context has shifted, the viewer has changed. Redundancy in art is the tool that allows an image to show the conditions of its existence, how each return announces that the world — and the viewer — are no longer quite the same.

The oldest cave walls we have are full of hands — dozens of them in a single chamber, and thousands across sites from France to Indonesia to Australia. It is one of the most widespread and enduring motifs in Ice Age art. Alongside these hands, the walls keep returning to the animals these early humans would see every day. Bison, horses, aurochs, deer, lions — all painted again and again, often layered over each other, sometimes by many different people across generations. From the beginning, art was born as return. The same child’s hand pressed to stone, the same animal traced in movement, the same gesture repeated again and again and again.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to the digital meadow to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.