Your recession indicators are sexist

the economy is more than skirt lengths and lipstick sales

Women want to indulge in small luxuries.

“Indulgence”, in our current cultural imagination, is an inherently feminine act. To indulge is to reveal a feminine weakness for triviality and ornamentation. Consumptive, impulsive, frivolous—all conjure the image of ‘Mrs. Consumer’, an economically irresponsible shopaholic in pursuit of material pleasure.

Historically, society has had a tumultuous relationship with Mrs. Consumer.

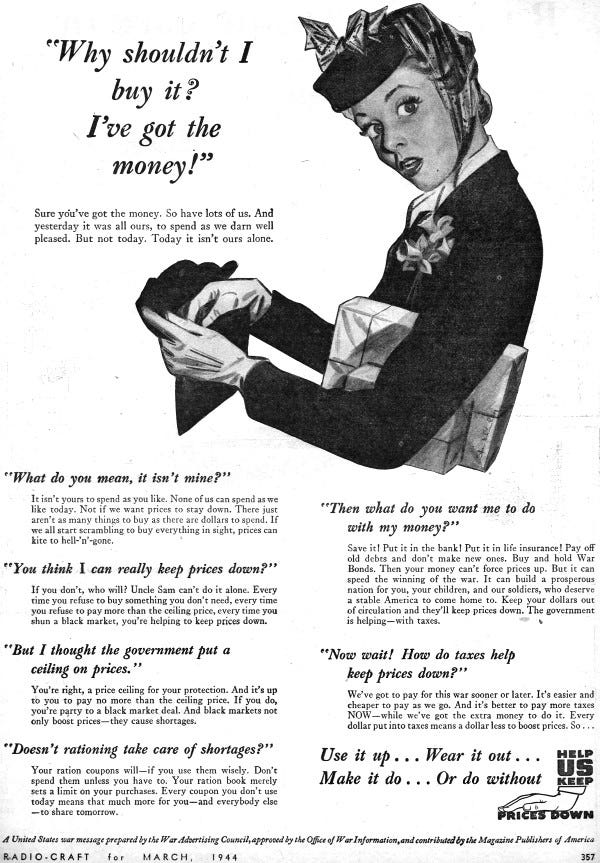

In the post-Great Depression and World War II eras, women were deliberately sought out as economic saviors. Housewives were urged to spend more to stimulate recovery and sustain consumer capitalism. Advertisements and campaigns framed shopping as a civic duty, a form of “pocketbook patriotism” that would rebuild the nation. Women were encouraged to purchase household appliances and new fashions, despite rationing, to signal confidence in postwar prosperity. “The republic’s future lay in the hands that fished through the purse; inflation and economic collapse would result if American women continued to hoard.”1

But this new dependance on women would not be seen as sensible for long. The same structures that pushed consumption would later label women as indulgent and wasteful. Their patriotic shopping soon became reflections of their vanity, their spending becoming a moral failing. Media now warned of the dangerous housewife draining family resources on unnecessary fashion and beauty products. “Celebrating Mrs. Consumer’s buying power also offered opportunities to criticize women for their irresponsibilities in handling it.”

Walter Pitkin, a popular self-help author and radio commentator, described women as the “economic imbecile” of the 1930s.

For Pitkin, female consumers were incapable of reason, abstraction, or calculation. They were by nature consumers, ‘closer to our primordial animality’ than men, the producers…they wasted industry’s resources by insatiable demands for meaningless style changes and cheap shoddy goods for variety. Pitkin charged that their devotion to ephemeral goods and their extravagance caused and prolonged the Depression. Women were unable to buy wisely for themselves and their families; their irrational demands curtailed the production of necessary commodities…For Pitkin, women caused the Depression and could not cure it.

—Charles McGovern, Sold American: Consumption and Citizenship

Even as the image of Mrs. Consumer shifted across the decades, the underlying anxieties about women’s spending remained. Whenever economic anxieties return, so does another version of Mrs. Consumer. And today she has reappeared as a new cultural lexicon: the “recession indicator”.

These indicators are small consumer trends read as unofficial signs of economic decline. Luxury lipstick sales. Longer skirts. Empty nail salons. “Recession blonde.” Lingerie as outerwear. Boxed hair dye. DIY manicures. Taller heels. Skinny jeans. Office wear at the club. Peplum tops.

Each of these is offered as a reflection of the economy’s state through women’s consumption and habits. Even if framed as jokes, the message remains that in times of economic anxiety, we turn to women—their spending and self-presentation—as both cause and symptom.

These recurring narratives about women’s consumption reveal the deeper power structures at play. Pierre Bourdieu, in his Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste (1979), introduces the concept of ‘symbolic violence’. He writes that it is a “gentle, invisible, pervasive violence…exercised upon a social agent with his or her complicity”. It works by making social hierarchies and inequalities appear natural and inevitable, so that the individuals come to accept the very systems that oppress them. Rather than being imposed overtly, symbolic violence is internalized. People learn to see the world and themselves through categories defined by those in power. In Bourdieu’s analysis, judgments about taste, style, and consumption are never neutral, but encoded in expressions of social position and domination. They reinforce the idea that certain choices are superior while other are inferior, even when those distinctions are arbitrary or culturally constructed.

This symbolic violence doesn’t only operate in the lofty realm of academic theory but in everyday cultural narratives. From recession indicators like the ‘hemline theory’ to the ‘lipstick index’, there is a fixation on women’s spending that relies on a system framing women’s habits as both personal flaws and public signs. These “indicators” normalize the belief that women’s consumption is excessive or irrational, while at the same time positioning women as symbolic indicators of economic health or decline.

But, in reality, the only consistent truth to these “indicators” is their contribution in perpetuating gendered stereotypes of consumption and clothing.

Like the ‘hemline theory’, which remains a popular “recession indicator” despite the little evidence to support it beyond cherry-picked historical moments. The theory suggests that there is a direct correlation between the length of women’s skirts and the state of the economy. During good times, hemlines go up. During times of financial struggle, hemlines go down. It might seem intuitive at first—shorter skirts during the carefree Roaring Twenties and longer ones during the somber Great Depression.

But like many retrospective narratives, its “accuracy” lies in hindsight, not predictive power.

The popularity of mini skirts in the 1960s, often seen as textbook evidence of this theory, did not occur only during a time of economic growth, but one marked by second-wave feminism, civil rights, and youth rebellion. Similarly, though the 2008 recession saw a resurgence of midi and maxi skirts, fashion trends were also largely influenced by the rise of fast fashion and global trends. Economic anxiety was not the sole factor shaping either of these fashion choices.

The ‘lipstick index’ is another popular theory that claims that luxury lipstick sales increase during recessions. It was created not by an economist, but by the then-chairman of Estée Lauder who observed a spike in lipstick sales following the 2001 recession. The logic is that, apparently, when female consumers cannot afford luxury goods, like designer handbags or vacations, they turn to small, affordable indulgences. Lipstick, then, becomes a kind of recession treat for them, a small splurge offering the illusion of normalcy.

But, like the ‘hemline theory’, the ‘lipstick index’ falters when tested against a broader range of data. While lipstick sales may have spiked in 2001, the pattern doesn’t reflect across other recessions. During the 2008 financial crisis, cosmetic sales overall declined—lipstick included.2 Rather than compensating for a lack of big spending, consumers seemed to decrease their non-essential purchases as a whole.

Beneath the theory also lies a familiar stereotype—that women, even in times of financial hardship, will prioritize vanity. The idea that women will choose beauty products over practical goods, that lipstick is somehow an indispensable need, only furthers the narrative that women are irrational and self-indulgent consumers. Through casual belief in this index as economic “wisdom”, it naturalizes the expectation that women will always find a way to consume, no matter the cost.

In this light, these theories and indexes become not simply quirky economic indicators, but symptoms of symbolic violence. They subtly discipline women’s choices and perpetuate hierarchies that normalize inequality and stereotyping. The act of reducing economic complexity to women’s hemlines or lipstick purchases is a way to keep women predictable and accountable to a gaze that doesn’t see them as independent economic agents, only as signs.

The irony here is only sharpened when we consider the realities these narratives obscure: Women, on average, earn less than men. Women are more likely to work lower-paying, part-time, or care-based jobs. Women are more likely to work jobs especially vulnerable to layoffs and instability during economic downturns. Women are more likely to be single parents. Women are disproportionately tasked with unpaid domestic labor. When the economy fluctuates, it is often women’s disposable income that falters first.

Yet this so-called “return to frugality” is framed not as a consequence of long-standing systemic inequalities in pay and labor, but as a temporary response to the current economic moment. A woman dyeing her own hair or skipping a nail appointment is not because she’s systemically disadvantaged and has been for decades, but because the market is fluctuating at that particular moment.

The very systems that deny women equal economic footing turn around and use the effects of that inequality as an indicator of crisis. Mrs. Consumer’s agency is reduced to the choices she can afford within a limited set of options. But then, once she makes those constrained choices, she is blamed for or made symbolic of the very instability she herself is a victim of.

The narrative shifts focus away from the wage gap and systemic inequality to, instead, focus on her visible economizing at a particular moment in time. But women, on average, are more likely than men to be frugal. Not only during crises, but as a constant adaptation to systemic wage disadvantages.3 What is framed as a ‘sudden shift’ in consumption is often not actually a departure from past behavior, but simply a moment when her long-standing economic frugality becomes focused on as an index of economic anxiety.

What’s also missing from this narrative is not only women’s unequal position as consumers, but the complete erasure of their role in production, ownership, and creation. Our cultural fixation on what women buy renders the labor they perform and the industries they sustain invisible. There is a structural refusal to recognize women as economic agents beyond their purchasing power.

Feminized consumption plays a pivotal role in stabilizing capitalist markets, especially in moments of crisis. Angela McRobbie has argued that post-feminist consumer culture recasts women’s agency as the freedom to choose, or to buy, which redirects political demands into lifestyle and aesthetic choices. Women are encouraged to manage risk through shopping and appearance to stabilize the economy and mask deeper economic instability. The system needs her to consume, just as it needs her unpaid labor to sustain the economy’s invisible frameworks.

What becomes clear is that women’s consumption is not merely a personal choice, but one historically manipulated to fit larger societal narratives. In Bourdieu’s terms, this reframing operates as a form of symbolic violence where systemic inequality is transformed into an individualized sign that women themselves are expected to monitor and regulate.

If women’s consumption is continuously framed as a public gauge of economic health, then women will inevitably learn to scrutinize their own behavior. Their purchases, appearances, and small indulgences become not simply personal choice, but signs of collective economic meaning.

In Bourdieu’s theory, the power of symbolic violence lies not in overt coercion, but in making hierarchies and judgements feel natural. It becomes so natural that individuals begin to police themselves according to the very standards that subordinate them. Women post their “recession blonde” or self-painted nails with a self-aware irony, but this irony does not subvert the stereotype, it resigns the woman to her economic role. It becomes a mode of “cruel optimism”, which offers fleeting consolation with sustaining an attachment to structures that cause harm. These jokes acknowledge these stereotypes, even if the woman is not aware of it, and it becomes an acceptance that her consumption is public economic symbol. Online platforms reward these gestures of self-surveillance through visibility and virality, fostering a participatory spectacle in which women volunteer themselves—consciously or not—as signs to be read and decoded within a harmful narrative.

Even if posted ironically, they still participate in a discourse that centers women’s value on what they buy or wear. The effect is a feedback loop in which women perform the very scripts they’re expected to perform and reinforce the idea that their primary economic role is consumption rather than production or ownership.

Mrs. Consumer is not a participant in the economy so much as a figure onto whom the economy’s instability is projected. Her choices are scrutinized and pathologized, while the larger forces limiting her economic power go undiscussed. And as long as we continue to read the economy through gendered recession indicators, women will remain trapped in the symbolic role of Mrs. Consumer.

Thank you for reading. If you would like to support my work and help keep my content free, please consider leaving a tip. Any and all support is greatly appreciated!

babe wake up, new essay from the digital meadow

"The system needs her to consume, just as much as her unpaid labor..." is profound and drives home your point. Loved this post